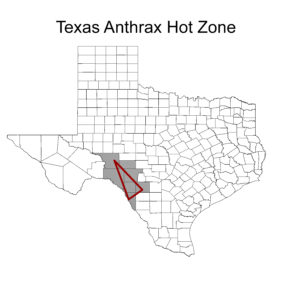

Grey counties indicate where Anthrax is most prevalent based on anthrax Cases reported to the Texas Animal Health Commision. The red Triangle indicated the hot zone for Anthrax cases in Texas.

Anthrax is a very old disease. The disease was clinically described in the 1700s, but descriptions of the disease have existed since ancient times and are believed to have been in the bible (1491 BC), in Homer’s story the Iliad (1228 BC), and in Aristotle’s History of Animals (333 BC). While anthrax can be found around the word, outbreaks are rare except in geographically-defined areas where cases occur often enough for the disease to be considered endemic. In North America, endemic areas include some western and mid-western states along with portions of Canada. In Texas there is an endemic region in the southwestern corner of the state, but anthrax is diagnosed occasionally in almost all areas of Texas.

Anthrax is caused by a spore-forming bacteria called Bacillus anthracis. The bacterial spores are resistant to heat, sunlight, drying, many disinfectants, and can survive in the environment for decades. Even in a laboratory setting, it can take up to 10 minutes in boiling water to destroy the bacteria, and at slightly less than boiling (98*C), the bacteria can persist for up to 30 minutes. These characteristics make it very difficult to prevent re-infection after an outbreak, but chances of re-infection can decrease over time if the soil is left undisturbed.

Animals with herbivorous diets (domestic and wild) are most sensitive to anthrax infections and more likely to die due to infection. Omnivores and carnivores are more resistant, and even if infected are capable of recovering. For livestock, there are annual vaccines that can be administered in endemic regions and even treatment options for unexpected outbreaks. Wild herbivores, especially ruminates (white-tailed deer, gazelles, antelopes), are highly susceptible to anthrax and can sometimes expire with the only symptom being sudden death.

Feral hogs in the hot zone with an unknown cause of death should not be dissected or processed. Photo by Jon McIntyre.

Direct transmission of anthrax from one live animal to another is not common. Herbivorous animals are often exposed to anthrax spores by consuming infected soil or plant materials while foraging. Omnivores and carnivores are frequently exposed through contact with infected carcasses, which is why appropriate carcass disposal is so important during an outbreak. Current recommendations for carcass disposal include burning in place so that only ashes remain, if burning is not an option the carcass should be buried deeply (in place) to prevent scavenging. Carcasses suspected having died of anthrax should not be opened (even for necropsy purposes) to prevent contaminating the area with spores and possible human exposure.

Cutaneous anthrax infection. Photo Credit AFIP; Center for Food Security and Public Health at Iowa State University, College of Veterinary Medicine

Anthrax is a zoonotic disease, meaning that it can be transferred to humans. Anthrax in humans can occur through cutaneous, gastrointestinal, or inhalation infections. Cutaneous infections are most common and occur when the bacteria enter the body through a cut or scrape. This form typically incubates for 7 to 10 days before showing symptoms and is rarely fatal to humans if treated early with antibiotics. The gastrointestinal form of infection can be more severe, but still treatable if diagnosed early. Gastrointestinal infections typically occur from eating infected undercooked meat. Inhalation infections are the most severe type of anthrax infection and are often fatal without immediate treatment. Inhalation infections rarely occur with natural anthrax exposure but have occurred in bioterrorism events.

Swine are omnivores and therefore susceptible to anthrax infections, but likely to survive. At this time, the effect of feral hogs on anthrax prevalence has not been defined, but some of their behaviors could be important in the ecology of this disease system. Feral swine are known to opportunistically feed on carcasses of livestock and wildlife, and regularly disturb soil through wallowing and rooting. These behaviors have the potential to further spread anthrax spores, but further study is needed.

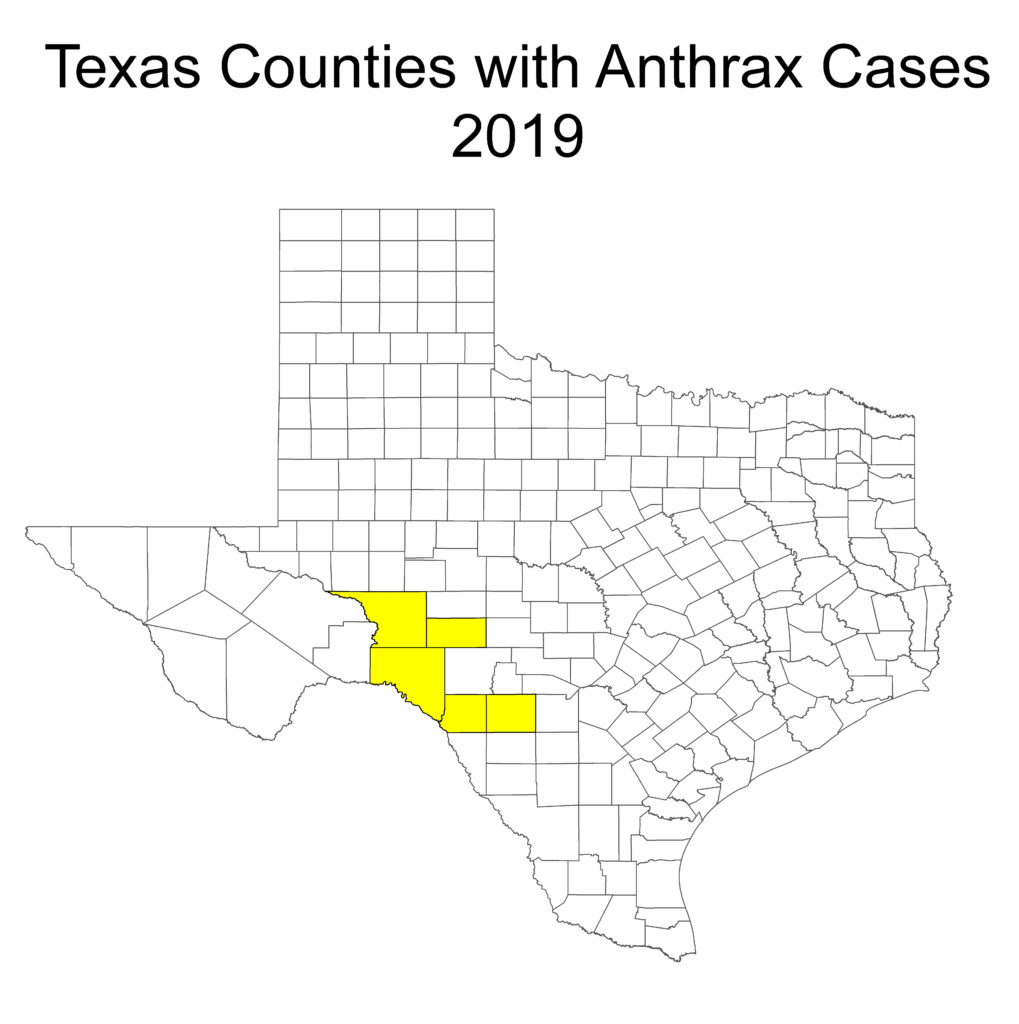

Recent Anthrax Reports:

Data provided by laboratory confirmed cases with Texas Animal Health Commision.

For more information on Anthrax, check out this Extension Publication.